Pfizer’s Power

In February, Pfizer was accused of “bullying” governments in COVID vaccine negotiations in a groundbreaking story by the Bureau of Investigative Journalism.[1] A government official at the time noted, “Five years in the future when these confidentiality agreements are over you will learn what really happened in these negotiations.”[2]

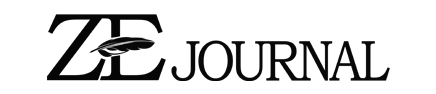

Public Citizen has identified several unredacted Pfizer contracts that describe the outcome of these negotiations. The contracts offer a rare glimpse into the power one pharmaceutical corporation has gained to silence governments, throttle supply, shift risk and maximize profits in the worst public health crisis in a century. We describe six examples from around the world below.[3]

Pfizer’s demands have generated outrage around the world, slowing purchase agreements and even pushing back the delivery schedule of vaccines.[16] If similar terms are included as a condition to receive doses, they may threaten President Biden’s commitment to donate 1 billion vaccine doses.[17]

High-income countries have enabled Pfizer’s power through a favorable system of international intellectual property protection.[18] High-income countries have an obligation to rein in that monopoly power. The Biden administration, for example, can call on Pfizer to renegotiate existing commitments and pursue a fairer approach in the future. The administration can further rectify the power imbalance by sharing the vaccine recipe, under the Defense Production Act, to allow multiple producers to expand vaccine supplies.[19] It can also work to rapidly secure a broad waiver of intellectual property rules (TRIPS waiver) at the World Trade Organization.[20] A wartime response against the virus demands nothing less.

1. Pfizer Reserves the Right to Silence Governments.

In January, the Brazilian government complained that Pfizer was insisting on contractual terms in negotiations that were “unfair and abusive.”[21] The government pointed to five terms that it found problematic, ranging from a sovereign immunity waiver on public assets to a lack of penalties for Pfizer if deliveries were late. The Bureau of Investigative Journalism soon published a scathing story on Pfizer’s vaccine negotiations.[22]

Less than two months later, the Brazilian government accepted a contract with Pfizer that contains most of the same terms that the government once deemed unfair.[23] Brazil waived sovereign immunity; imposed no penalties on Pfizer for late deliveries; agreed to resolve disputes under a secret private arbitration under the laws of New York; and broadly indemnified Pfizer for civil claims.[24]

The contract also contains an additional term not included in other Latin American agreements[25] reviewed by Public Citizen: The Brazilian government is prohibited from making “any public announcement concerning the existence, subject matter or terms of [the] Agreement” or commenting on its relationship with Pfizer without the prior written consent of the company.[26] Pfizer gained the power to silence Brazil.

Brazil is not alone. A similar nondisclosure provision is contained in the Pfizer contract with the European Commission and the U.S. government.[27] In those cases, however, the obligation applies to both parties.

For example, neither Pfizer nor the U.S. government can make “any public announcement concerning the existence, subject matter or terms of this Agreement, the transactions contemplated by it, or the relationship between the Pfizer and the Government hereunder, without the prior written consent of the other.”[28] The contract contains some exceptions for disclosures required by law. It is not clear from the public record whether Pfizer has elected to prohibit the U.S. from making any statements thus far. The E.C. cannot include in any announcement or disclosure the price per dose, the Q4 2020 volumes, or information that would be material to Pfizer without the consent of Pfizer.[29]

2. Pfizer Controls Donations.

Pfizer tightly controls supply.[30] The Brazilian government, for example, is restricted from accepting Pfizer vaccine donations from other countries or buying Pfizer vaccines from others without Pfizer’s permission.[31] The Brazilian government also is restricted from donating, distributing, exporting, or otherwise transporting the vaccine outside Brazil without Pfizer’s permission.[32]

The consequences of noncompliance can be severe. If Brazil were to accept donated doses without Pfizer’s permission, it would be considered an “uncurable material breach” of their agreement, allowing Pfizer to immediately terminate the agreement.[33] Upon termination, Brazil would be required to pay the full price for any remaining contracted doses.[34]

3. Pfizer Secured an “IP Waiver” for Itself.

The CEO of Pfizer, Albert Bourla, has emerged as a strident defender of intellectual property in the pandemic. He called a voluntary World Health Organization effort to share intellectual property to bolster vaccine production “nonsense” and “dangerous.”[35] He said President Biden’s decision to back the TRIPS waiver on intellectual property was “so wrong.”[36] “IP, which is the blood of the private sector, is what brought a solution to this pandemic and it is not a barrier right now,” claims Bourla.[37]

But, in several contracts, Pfizer seems to recognize the risk posed by intellectual property to vaccine development, manufacturing, and sale. The contracts shift responsibility for any intellectual property infringement that Pfizer might commit to the government purchasers. As a result, under the contract, Pfizer can use anyone’s intellectual property it pleases—largely without consequence.

At least four countries are required “to indemnify, defend and hold harmless Pfizer” from and against any and all suits, claims, actions, demands, damages, costs, and expenses related to vaccine intellectual property.[38] For example, if another vaccine maker sued Pfizer for patent infringement in Colombia, the contract requires the Colombian government to foot the bill. At Pfizer’s request, Colombia is required to defend the company (i.e., take control of legal proceedings.)[39] Pfizer also explicitly says that it does not guarantee that its product does not violate third-party IP, or that it needs additional licenses.

Pfizer takes no responsibility in these contracts for its potential infringement of intellectual property. In a sense, Pfizer has secured an IP waiver for itself. But internationally, Pfizer is fighting similar efforts to waive IP barriers for all manufacturers.[40]

4. Private Arbitrators, not Public Courts, Decide Disputes in Secret.

What happens if the United Kingdom cannot resolve a contractual dispute with Pfizer? A secret panel of three private arbitrators—not a U.K court—is empowered under the contract to make the final decision.[41] The arbitration is conducted under the Rules of Arbitration of the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC). Both parties are required to keep everything secret:

The Parties agree to keep confidential the existence of the arbitration, the arbitral proceedings, the submissions made by the Parties and the decisions made by the arbitral tribunal, including its awards, except as required by Law and to the extent not already in the public domain.[42]

The Albania draft contract and Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Dominican Republic, and Peru agreements require the governments to go further, with contractual disputes subject to ICC arbitration applying New York law.[43]

While ICC arbitration involving states is not uncommon, disputes involving high-income countries and/or pharmaceuticals appear to be relatively rare.[44] In 2012, 80% of state disputes were from Sub-Saharan Africa, Central and West Asia, and Central and Eastern Europe.[45] The most common state cases were about the construction and operation of facilities.[46] In 2020, 34 states were involved in ICC arbitrations.[47] The nature of state disputes is not clear, but only between 5 to 7% of all new ICC cases, including those solely between private parties, were related to health and pharmaceuticals.[48]

Private arbitration reflects an imbalance of power. It allows pharmaceutical corporations like Pfizer to bypass domestic legal processes. This consolidates corporate power and undermines the rule of law.

5. Pfizer Can Go After State Assets.

The decisions reached by the secret arbitral panels described above can be enforced in national courts.[49] The doctrine of sovereign immunity can sometimes, however, protect states from corporations seeking to enforce and execute arbitration awards.

Pfizer required Brazil, Chile, Colombia, the Dominican Republic, and Peru to waive sovereign immunity.[50] In the case of Brazil, Chile and Colombia, for example, the government “expressly and irrevocably waives any right of immunity which either it or its assets may have or acquire in the future” to enforce any arbitration award (emphasis added).[51] For Brazil, Chile, Colombia, and the Dominican Republic, this includes “immunity against precautionary seizure of any of its assets.”[52]

Arbitral award enforcement presents complex questions of law that depend on the physical location and type of state asset.[53] But the contract allows Pfizer to request that courts use state assets as a guarantee that Pfizer will be paid an arbitral award and/or use the assets to compensate Pfizer if the government does not pay.[54] For example, in U.S. courts, these assets could include foreign bank accounts, foreign investments, and foreign commercial property, including the assets of state-owned enterprises like airlines and oil companies.[55]

6. Pfizer Calls the Shots on Key Decisions.

What happens if there are vaccine supply shortages? In the Albania draft contract and the Brazil and Colombia agreement, Pfizer will decide adjustments to the delivery schedule based on principles the corporation will decide. Albania, Brazil, and Colombia “shall be deemed to agree to any revision.”[56]

Some governments have pushed back on Pfizer’s unilateral authority for other decisions. In South Africa, Pfizer wanted to have the “sole discretion to determine additional terms and guarantees for us to fulfill the indemnity obligations.”[57] South Africa deemed this “too risky” and a “potential risk to [their] assets and fiscus.”[58] After delays, Pfizer reportedly conceded to remove this “problematic term.”[59]

But others have not been as successful. As a condition to entering into the agreement, the Colombian government is required to “demonstrate, in a manner satisfactory to Suppliers, that Suppliers and their affiliates will have adequate protection, as determined in Suppliers’ sole discretion” (emphasis added) from liability claims.[60] Colombia is required to certify to Pfizer the value of the contingent obligations (i.e., potential future liability), and to start appropriating funds to cover the contingent obligations, according to a contribution program.[61]

Pfizer’s ability to control key decisions reflects the power imbalance in vaccine negotiations. Under the vast majority of contracts, Pfizer’s interests come first.

A Better Way

Pfizer’s dominance over sovereign countries poses fundamental challenges to the pandemic response. Governments can push back. The U.S. government, in particular, can exercise the leverage it holds over Pfizer to require a better approach. Empowering multiple manufacturers to produce the vaccine via technology transfer and a TRIPS waiver can rein in Pfizer’s power. Public health should come first.

- Source : Zain Rizvi