Taboo: Why Is Africa the Global COVID ‘Cold Spot’ and Why Are We Afraid to Talk About It?

The first COVID-19 case in Africa was confirmed on February 14th, 2020, in Egypt. The first in sub-Saharan Africa appeared in Nigeria soon after. Health officials were united in a near-panic about how the novel coronavirus would roll through the world’s second most populous continent. By mid-month, the World Health Organization (WHO) listed four sub-Saharan countries on a “Top 13” global danger list because of direct air links to China. Writing for the Lancet, two scientists with the Africa Center for Disease Control outlined a catastrophe in the making:

With neither treatment nor vaccines, and without pre-existing immunity, the effect [of COVID-19] might be devastating because of the multiple health challenges the continent already faces: rapid population growth and increased movement of people; existing endemic diseases… re-emerging and emerging infectious pathogens… and others; and increasing incidence of non-communicable diseases.

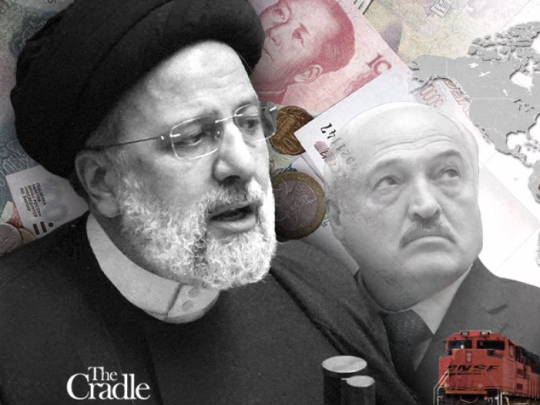

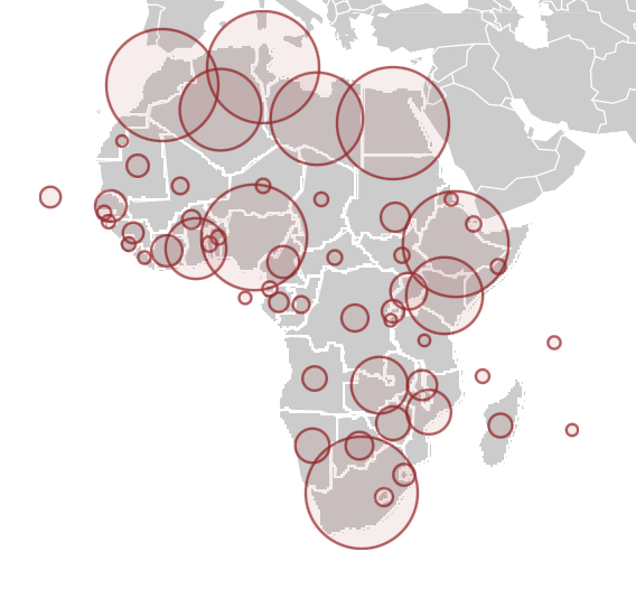

Many medical professionals predicted that Africa could spin into a death spiral. “My advice to Africa is to prepare for the worst, and we must do everything we can to cut the root problem,” Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, the first African director-general of the WHO, warned in March 2020. “I think Africa, my continent, must wake up.” By spring, the WHO was projecting 44 million or more cases in Africa and the World Bank issued a map of the continent colored in blood red, anticipating that the worst was imminent:

These dire warnings seemed to make sense. After all, two-thirds of the global extreme poor population (63 percent) live in sub-Saharan Africa. According to the World Bank, more than 40 percent of the region lives in extreme poverty beset by unhygienic environments, conflict, fragmented healthcare and education systems, and dysfunctional leadership—all factors that could light a match to the tinder of the SARS-CoV-2 outbreak. Scientists say that most African countries lack the capacity and expertise to manage endemic deadly diseases like malaria.

Each individual’s risk of dying from a particular disease tends to reflect access to adequate healthcare and underlying health conditions (co-morbidities). Those factors have proved to be a lethal mix in poorer communities in the US, Brazil, the UK, and other countries, with lower income groups—often ethnic and racial minorities—dying at disproportionately high rates. Africa seemed ripe for catastrophe.

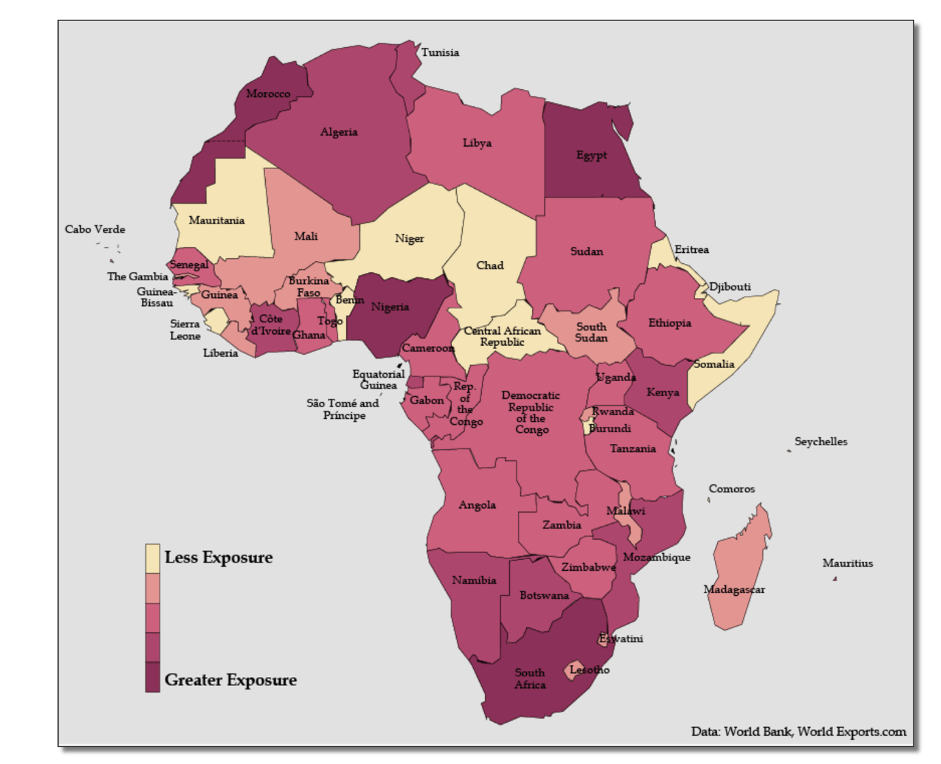

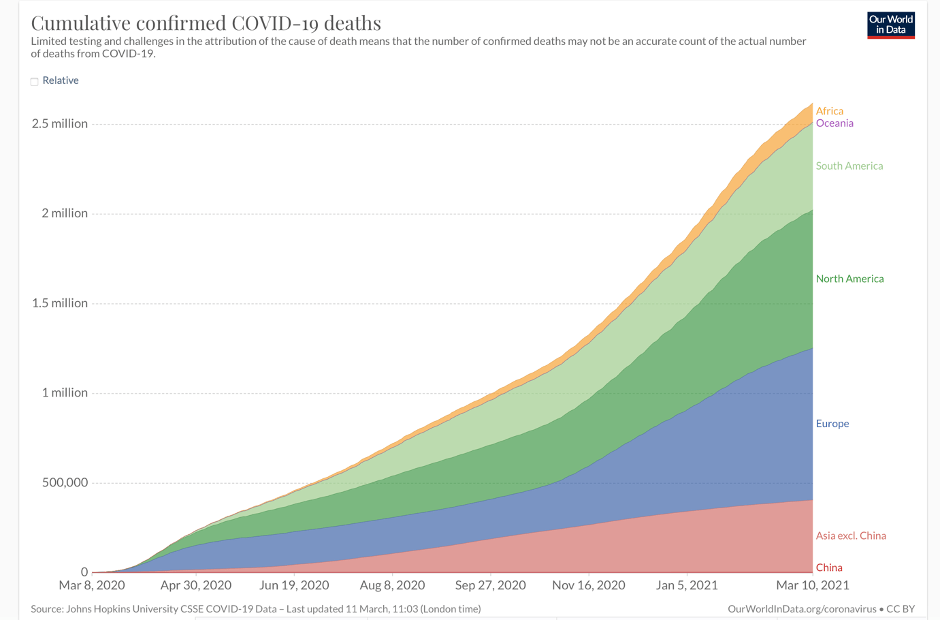

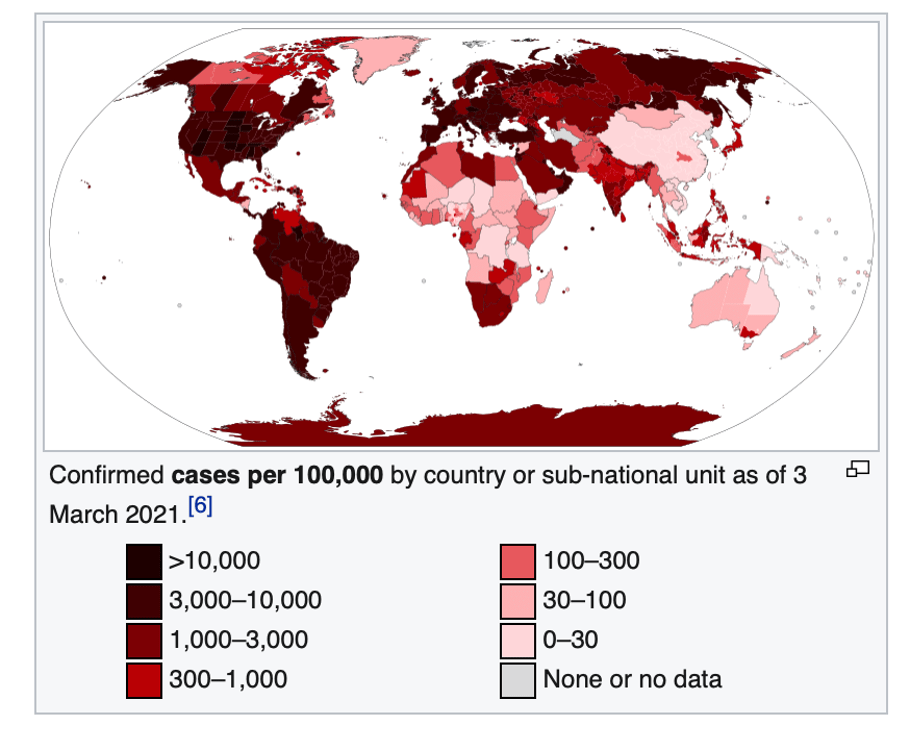

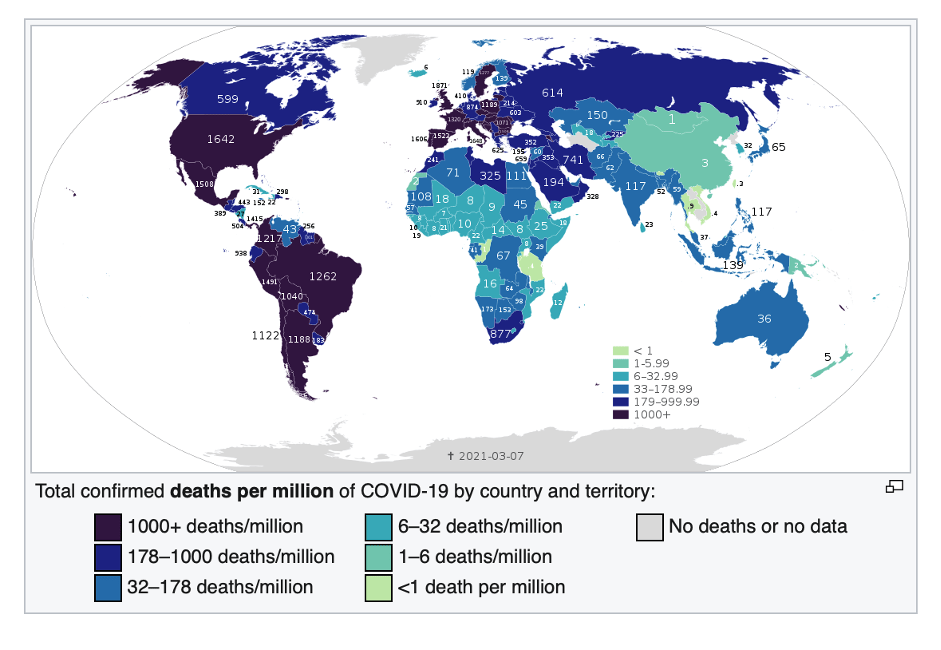

But disaster never came. Africa has not been affected on anything like the scale of most countries in Asia, Europe, and North and South America. (The major exceptions being China, Taiwan, Australia, and New Zealand, which zealously enforced lockdowns.) In fact, the vast African sub-continent south of the Sahara desert, more than 1.1 billion people, has emerged as the world’s COVID-19 “cold spot,” as illustrated by an ECDC map reproduced by BBC and by graphics like these:

The latest statistics show about four million cases and 107,000 coronavirus-related deaths, concentrated mostly in the Arab majority countries north of the Sahara. Except for South Africa—the most multiracial of the black-majority countries—and Nigeria, sub-Saharan Africa has largely been spared. And these startling low case and death statistics come even as Africa has the lowest vaccination rate in the world—less than one dose administered per 100 people, and with many countries having given none to the general population.

Europe has less than two-thirds of the population of Africa, but by mid-March 2021, it had 39 million cases and almost 900,000 deaths—900 percent more. The US, with less than a third of the population of Africa, has approximately 30 million cases and 535,00 deaths as of this writing, thousands of percent more on a per capita basis than Africa. In other words, the US, Europe, and parts of South America are experiencing far more than 1,000 deaths per million while most of sub-Saharan Africa has between 0.5 and 25 deaths per million, according to stats updated regularly by Wikipedia.

Journalists and even some scientists have been twisting themselves into speculative pretzels trying to explain this phenomenon. Theories range from sub-Saharan Africa’s “quick response” (no); favourable climate (which has not protected tropical sections of Brazil, Peru, and other warmer climes in South America); and good community health systems (directly contradicted by WHO and Africa CDC).

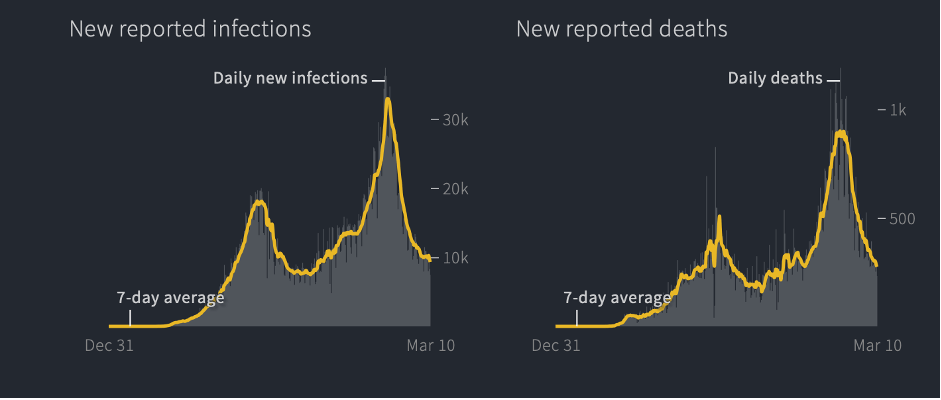

In each of those articles acknowledging these “puzzling” statistics, journalists were sure to suggest that Armageddon might be right around the corner. “Experts fear a more devastating second surge,” warned National Geographic in late December, although there was no first surge and just two weeks before Africa’s tiny December uptick (driven almost entirely by the mutant variant in South Africa) turned back downward, according to Reuters:

Why Africa has been less impacted by COVID-19

So what’s going on here? And why are the media and most scientists so unwilling to engage one of the most plausible science-based factors: that black Africans appear to be protected, at least in part, by their ancestry? Combined with the fact that sub-Saharan Africa is the youngest region in the world—youth brings fewer co-morbidities and age is the most significant factor in contracting and dying from COVID-19—ancestry is likely a significant contributing factor to sub-Saharan Africa’s comparatively modest case and death count. With the notable exception of a research project in Hawai’i, scientists tend to shy away from exploring the population genetics angle, almost certainly fearful of stirring the embers of “race science.”

“It is really mind boggling why Africa is doing so well, while in US and UK, the people of African ancestry are doing so poorly,” Maarit Tiirikainen, a cancer and bioinformatics researcher at the University of Hawai’i Cancer Center, told us in an email. Dr. Tiirikainen is a lead researcher in a joint project at the University of Hawai’i and LifeDNA in what some believe is a controversial undertaking considering the taboos on “race” research. They are attempting to identify “those that are most vulnerable to the current and future SARS attacks and COVID based on their genetics.”

Blacks (along with other ethnic minorities) in the US and Great Britain who have contracted COVID-19 have generally fared worse than whites. “For the latter, it seems the Western socioeconomics may play a major role. There may also be genetic differences in immune and other important genes,” Dr Tiirikainen wrote. (The terms “black” and “white” are used here as shorthand for more cumbersome expressions like “those of African descent” or “people of European ancestry”—they are not science-based population categories.) Dr. Tiirikainen, like many candid researchers in this field, is skeptical that social and environmental factors alone can account for the extraordinarily low COVID-19 African infection and death rates. It is not because Africa took extraordinary steps to insulate itself as the pandemic spread. Healthcare remains fragmented at best and COVID information outreach has been limited by scant resources.

At the end of March 2020, when much was still to be learned about the science of COVID-19, the co-authors of this article—the Genetic Literacy Project’s Jon Entine and contributing science journalist Patrick Whittle—discussed some of the potential reasons in the article “What’s ‘race’ got to do with it?” Following discussions with many experts, we decided not to reflexively exclude genetic explanations, which are a taboo subject. Rather, we examined the panoply of likely causes, rejecting the a priori Western prejudice that often excludes evidence that might be linked to population-level genetics and group differences for fear of “racializing” the analysis. We are obviously aware that skin color is not a recognized science-based population concept. Given the racist history of biological beliefs about human differences, addressing the fact of ancestrally-based genetic differences must be pursued carefully.

Why even discuss possible genetic factors? Because biases among researchers and public policy officials could undermine the development and deployment of treatments and antiviral vaccines for all of us, but particularly for more vulnerable populations in Africa and in the African diaspora. Blacks and other racial minorities in the US, Latin America, and the UK are more likely to suffer chronic health problems. For example, in the US, blacks are more than 50 percent likelier to report having poor health as compared to whites, and more than two-thirds of black adult women are overweight. Developing therapies for at-risk populations is critical. Those with genetic resistance to infection or who may be genetically protected in some degree from developing symptoms could help scientists develop treatments for all. Lives are at stake.

So let’s dip into these murky waters. Could our ancestry, which defines our genetic make-up, play a role in susceptibility to COVID or other viruses?

Environmental-based black-white differences impact COVID vulnerability

There are some significant non-genetic factors behind the Africa numbers. In the case of disease susceptibility, social and environmental explanations have played a huge role in the limited impact of COVID-19 in Africa to date. For one thing, the apparent low incidence of cases and deaths could be due in part to under-reporting or limited testing, although testing has been surging in Africa even as the number of cases remained flat.

The most significant environmental factor, scientists say, is age. The average age of Europeans is 43; it’s 38 in the US; across the African continent, it is 18. The average age in Niger, Mali, Uganda, and Angola is under 16. Roughly a quarter of the population in both Europe and North America is over 60-years old, while in Africa, the 60+ age cohort makes up only six percent of the population.

When infected, the young are also less likely to show symptoms, and asymptomatic people are not as likely to be tested, perhaps suppressing the numbers. Younger people are also, by and large, healthier. The average age of black Americans is about twice that of black Africans. Moreover, the deaths among African Americans—almost twice that of white and Asian Americans—have been almost exclusively concentrated among the elderly, many of whom suffer from multiple co-morbidities and less access to healthcare. That’s the opposite of the situation in Africa.

The younger African population may explain some of the disparities in deaths, but not all of them; the wealthier nations of Asia have managed the pandemic better than Europe and North America, despite having similarly older populations, and the virus is still raging in some South Asian countries. It also should be noted that age has often played the opposite role in surviving scourges. Malaria is historically the world’s deadliest disease, but age-related survival rates are the reverse of that with COVID-19, with the very young most at risk. In 2018, for example, most of the estimated 405,000 people who died from malaria were young children in sub-Saharan Africa. As may be the case for COVID-19, genetics trumps other risk factors.

Climate also may play a role, although here the data are mixed. Generally, the pandemic has spread more virulently in colder climes, with more temperate countries in Asia and Africa somewhat spared—though most of those countries, from Australia to China, Vietnam, and Taiwan, have undertaken massive tracing and have imposed near-universal shutdowns on occasion. But tropical parts of Brazil and Peru remain in crisis, exacerbated by a variant strain of the coronavirus.

Genetics and COVID

So, to what degree does ancestry play a role in our susceptibility to COVID-19? Unfortunately, there is a dearth of research on the genetics of African peoples, so it’s difficult to make too much of these fragmented examples. And despite Africa being the “cradle of humankind,” with its populations containing more human genetic variation than any other continent, black Africans and those of African descent remain woefully under-represented in genetic studies.

Given the historical research bias towards Eurasia and North America, almost 20 years after the sequencing of the human genome, the vast majority of genetic samples are of European ancestry (nearly 90 percent in 2017, with most of these from just three countries—Great Britain, the US, and Iceland). Recent pioneering surveys of African genomes are just now beginning to reveal that continent’s rich genetic legacy, replete with the merging and divergence of myriad ancestral populations.

What genetic factors could be impacting COVID-19 infection and death rates? Research and informed speculation are already underway. An earlier study on the possible contribution of genetics to the SARS-CoV-2 infection found significant population-based differences in ACE2 receptors that modulate blood pressure in the cells located in the lungs, arteries, heart, kidneys, and intestines. Africans are considerably less likely than East Asians to express the ACE2 receptors, though slightly higher than Europeans, the researchers believe. “There have been major differences in the rates of SARS-CoV-2 infection and the severe disease between the different geographic regions since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, even among young individuals,” Dr. Tiirikainen told us.

At least two studies show that blood type O could be associated with a lower risk of COVID-19 infection and reduced likelihood of severe outcomes, including organ complications. There is also some evidence that those with blood type A are more susceptible to COVID-19. The researchers did not find any significant difference in rates of infection between A, B, and AB types. About 37 percent of the world population is O+ and six percent is O-. About 50 percent of Africans have blood group O, the highest in the world.

It’s well established that certain HLA (human leukocyte antigens) alleles confer susceptibility to specific diseases. African-descended and European-descended populations implicate distinctively different immunity responses in dozens of diseases treatments. For example, it is extremely rare for people of unmixed black African ancestry to get ankylosing spondylitis, a rare type of arthritis. Whites are three times more likely to get it. The histocompatibility antigen HLA-B27, which does not exist in black Africans of unmixed ancestry, is present in eight percent of white and only about two to four percent of the black American population (reflecting racial mixing).

Susceptibility to the coronavirus is negatively associated with having a genetic propensity to absorb Vitamin C, as is the case with black African populations. Across Africa, roughly 50 percent of people carry the Vitamin C-friendly variant and in some African countries, it is as high as 70 percent. In the US, 41 percent of whites carry this variant, compared to 55 percent of blacks, and only 31 percent of Asians. There is also preliminary evidence to suggest that vitamin D supplements at high doses might help protect against becoming infected with COVID-19 or limiting serious symptoms. How might this relate to people of African ancestry? Blacks as a population group have markedly low levels of vitamin D.

Yet in a paradox, people of African ancestry who take Vitamin D supplements get no skeletal benefits from them. Their bones are naturally less brittle than those of other populations. Black Americans, for example, have significantly fewer incidences of falls, fractures, or osteopenia compared to white Americans. Could the factors that naturally protect the bone health of blacks also protect them against more serious COVID symptoms? At the moment, there are no clear explanations for the vitamin D “black paradox,” but scientists we talked to say there may be some genetic factors at play.

Genetics cut multiple ways

Are black Americans and those of African descent in general less genetically susceptible to some viruses or diseases other than COVID-19? The evidence is fragmentary. Contradicting racist early-20th century theories that “frail” blacks are more susceptible to disease, during the 1918 pandemic, the incidence of influenza was significantly lower in African Americans. And according to a 2016 study of swine flus, when exposed, “African Americans mounted higher virus neutralizing and IgG antibody responses to the H1N1 component of IIV3 or 4 compared to Caucasians.”

The relationship of genes to disease is often convoluted. Populations of African descent are simultaneously more prone to sickle cell anaemia (particularly prevalent south of the Sahara) and have natural, genetic-based defenses against malaria. This connection was noted over 50 years ago. And in a tragic twist, some genetic variants thought to reduce susceptibility to malaria are believed to increase vulnerability to the HIV virus. While fear of AIDS has receded in the West and in developing countries in Africa, HIV still infects tens of millions of people, with hundreds of thousands dying of the disease each year, mostly in Africa. Adult HIV prevalence is 1.2 percent worldwide but nine percent in sub-Saharan Africa.

In the US, where the national rate is 0.6 percent, African Americans account for 42 percent of new HIV infections despite being only 12 percent of the population. It’s now believed that a gene variant common in some African and African diaspora populations that protects against certain types of malaria increases susceptibility to HIV infection by 40 percent.

If this is indeed the case, it is an example of genes conferring both benefits and liabilities as populations evolved and moved around in different eras and different environments. In ancestral environments, malaria was the force selecting for variants that provided partial immunity; in the modern environment, HIV may be the force selecting against those unfortunate enough to carry these genetics and might partly explain the apparent reduced severity of COVID-19 in Africa.

Africa, DNA, and the historical dance of genes and environment

Does greater prior exposure to pathogens, including other recent coronaviruses, help explain why Africa is a COVID-19 cold spot, despite endemic poverty and a woeful health infrastructure? Conversely, in the more sanitized surroundings of the more developed world, people’s immune systems may be insufficiently “trained” to cope with novel disorders, such as COVID-19—what’s known as the “hygiene hypothesis.” According to this thesis, the very conditions expected to cause the rapid spread of the virus may instead have primed the immune system of native Africans to better resist this latest disease, along with antibodies gained through exposure to numerous infectious ailments since childhood. (This theory has also been used to explain the reduced impact of the coronavirus in India, relative to the size of its population.)

This is also how population-wide “herd immunity” is naturally selected across evolutionary time, with those genetically more resistant to specific diseases surviving and reproducing at greater rates than the more vulnerable. It’s known that the Black Death epidemic didn’t just wipe out millions of Europeans (a third of the population) during the 14th century; it also left a permanent, protective marker on the human genome, favoring those who carried immune system genes, who passed them on over subsequent centuries. Certainly, with disease a long-recognized feature of the living world, it is no surprise it is a major factor in Charles Darwin’s theory of natural selection. Darwin himself had seen the devastating effects of disease on indigenous peoples during the voyage of the Beagle, and it featured in his later account of human evolution (and extinction), Descent of Man.

Disease is also central to the convincing Guns, Germs & Steel thesis advanced by biogeographer Jared Diamond. According to Diamond, following the advent of agriculture in Eurasia (circa 10,000 years ago), the denser populations of the new farming societies were ideal breeding grounds for novel diseases (a process exacerbated by close contact with disease-bearing domesticated animals). Over millennia, newly-emerging diseases periodically swept along Eurasia’s trade routes, genetically selecting for disease-resistance among the surviving populations. Most relevant here is the grim historical consequence of this evolved genetic immunity among some populations but not others. In Diamond’s estimation, more than 90 percent of the indigenous peoples of the Americas—never before exposed to the deadly contagions of Eurasia—were wiped out within decades of the arrival of European colonists and invaders.

The New World disease apocalypse mirrors others that have plagued humankind for millennia. Recent genetic research suggests that Europe’s original Neolithic population may have been displaced by disease-resistant peoples from the East, 5,000 to 6,000 years ago. Once again, evolved population differences may have proved key, with newcomers’ longer exposure to the plague bacterium, Yersinia pestis, likely providing partial immunity not shared by the existing European populations. (The Black Death, the Spanish flu, and now COVID-19 are well-known historical examples of this process.)

There is also tantalizing emerging evidence that ancient coronaviruses drove natural selection for disease resistance in East Asia between 25,000 and 5,000 years ago, with “[t]hese adaptive events… limited to ancestral East Asian populations, the geographical origin of several modern coronavirus epidemics” [emphasis added]. Indeed, our newfound abilities to probe the secrets of ancient DNA also allow us to search even further back into human prehistory—and into the divergent evolutionary pathways followed by a distant human cousin, the Neanderthals.

Do Neanderthal genes increase the risk of COVID-19?

The answer is yes. In fact, the presence of a Neanderthal gene is the single biggest genetic risk factor for the novel coronavirus, roughly doubling the likelihood of getting the virus, according to a June 2020 study by researchers in Germany and Japan, Hugo Zeberg and Svante Pääbo. In follow-up research published in February 2021, they identified one haplotype that “is present at substantial frequencies in all regions of the world outside Africa. Given that Neanderthals were a branch of ancient humans seemingly confined to western Eurasia, sub-Saharan African populations never interbred with this sister-species except for the white minority population which migrated to the region. This particular stretch of Neanderthal DNA is carried by around 50 percent of South Asians, 16 percent of those of European descent, but not in any native Africans.”

Illustrating the complexity (and ironies) of evolution, the researchers suggest that these genes may have protected our distant cousins against pathogens found in their ancient environment, and were hence retained in some Eurasian populations subsequent to human-Neanderthal admixture. Now, however, these same genes may have a detrimental effect with the different COVID-19 pathogen.

In the words of the researchers, the immune response for carriers of these Neanderthal sequences “might be overly aggressive,” leading to potentially fatal reactions in those who develop severe COVID-19 symptoms. This explanation is analogous to the genetics of HIV susceptibility, with ancient-acquired advantageous genes now proving disadvantageous. Importantly, this could also be true for any human population, African or non-African, that may show a different response to any disease (although there is also a genetic variant from Neanderthals that is protective against severe COVID-19, albeit to a smaller degree).

Reviving an egregious, racist, un-scientific concept?

All populations and individuals are a mishmash of unique genes acquired from ancestral populations. Yet, while the evidence of divergent evolution between distinct human groups continues to accumulate, such evidence continues to cause disquiet.

Is it suspect—or even racist—to explore the relationship of disease to population? Although the historically problematic term “race” is considered a controversial subject, geneticists have long recognized genetic differences among populations in disease proclivities. Renowned population geneticist Neil Risch and colleagues addressed this issue years ago in a seminal paper, ‘Categorization of Humans in Bio-Medical Research: Genes, Race and Disease,’ writing:

We believe that identifying genetic differences between races and ethnic groups, be they for random genetic markers, genes that lead to disease susceptibility or variation in drug response, is scientifically appropriate… Every race and even ethnic group within the races has its own collection of clinical priorities based on differing prevalence of diseases.

Nevertheless, exploring this issue risks bringing opprobrium down on those who raise it. As Jared Diamond has written, “few scientists dare to study racial origins, lest they be branded racists just for being interested in the subject.” Given the racist history of biological beliefs about human differences (and, in this case, the xenophobic backdrop to the current COVID-19 pandemic), it is a topic that must be addressed with care, if directly and honestly.

As we’ve made clear, apparent differences in disease risk among populations need not have direct biological causes. With COVID-19, it is already well-established that age, obesity, and other pre-existing health problems bear on the severity of the disease, and these factors are unevenly distributed among different racial groups. Some risk indicators are more important than others; in the US, for example, age does not appear to be the key determining factor in the impact of COVID-19 across sub-populations; rather it’s more about “race” and economic class. The most common age for white Americans who have contracted the coronavirus is 58 years; for African Americans it is 27. Yet, despite being much younger on average, black Americans are much more likely than white Americans to contract, be hospitalized by, or die from the novel coronavirus.

The same is true among indigenous American, Hispanic communities, and Pacific Islanders in Hawai’i. The major mortality predictor so far is social inequality—deprivation, marginalization, inadequate access to healthcare, and the like. Some of those factors have also contributed to higher rates of co-morbidities among COVID-19-vulnerable minority populations.

Genetic and social factors should be examined simultaneously

What does all this mean? It’s complicated. There are appropriate concerns that incorporating population-based genetic explanations may trivialize the complexity of interaction between genes, environment, and society. Such criticism cuts both ways: just as an over-emphasis on genes may ignore crucial environmental factors, so too might a solitary focus on environment overlook relevant genetic influences. The historical misuse of facile “race” concepts to support odious hierarchies does not mean we should ignore possible genetic influences on the spread of the virus.

Unfortunately, a common but mistaken belief among those suspicious of genetic research is that those who argue that population genetics should play a critical role in assessing disease susceptibility embrace the discredited belief that genes determine outcomes. By this facile argument, if genes are implicated in susceptibility/resistance to coronavirus, they must override everything else.

But no serious scientist studying this complex issue is a determinist; that’s a notion decades out of date. Citing the tragically banal fact that that Americans of primarily African ancestry are more likely to die from COVID does not come close to “disproving” the very likelihood that the genetics of those of African descent might have certain “protective” genes. A more nuanced and non-deterministic assessment points to the continuous interaction between genes and environment. If genetics play a role in the apparent partial-immunity of native Africans to the coronavirus, similar influences for those of mixed African ancestry in the US and elsewhere could still be swamped by an onerous social environment faced by blacks and other minorities.

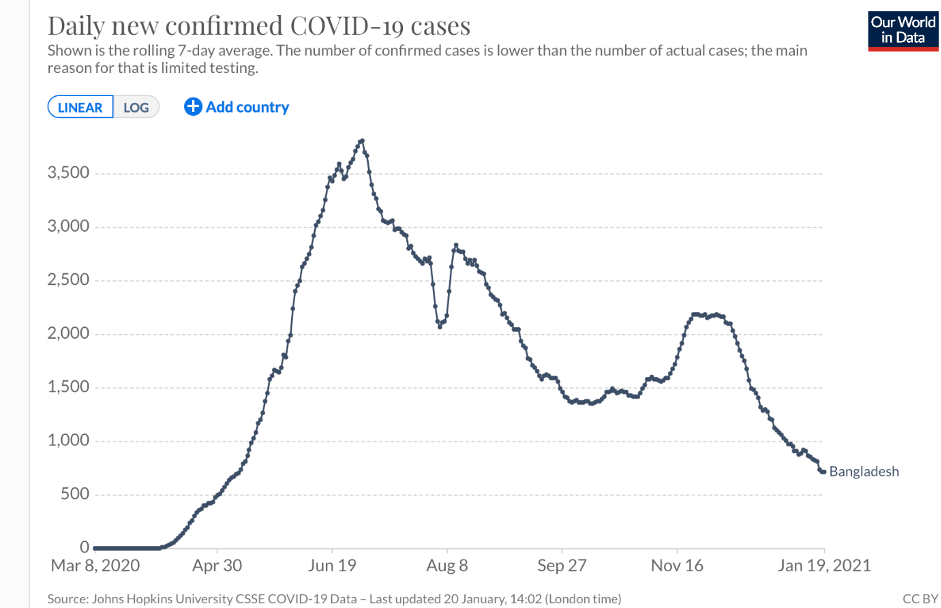

The subtle give-and-take of genetics and the environment may inform the experience of Africans of Bangladeshi descent. While UK-based Bangladeshis—a socially-disadvantaged minority group—are twice as likely to die from the coronavirus as the general British population, the COVID-related death totals in Bangladesh (8,000 deaths), is plummeting.

But the Bangladeshi example is also significant because it illustrates the complexity of the issue and conflicting narratives about genetics and the coronavirus. Bangladesh as a country is doing better than many countries which is both surprising and not so. The country ranks 57 out of 152 globally. The US ranks 143. The average age (25.7) is comparatively young. Like Africans, Bangladeshis might have been expected to have received some protection based on the “hygiene hypothesis.” But clearly there are myriad other factors at play, including the intriguing fact that Bangladeshis carry the gene cluster implicated as likely increasing the risk from COVID-19 (more than half the population, 63 percent, carry at least one copy of the risk haplotype). The interaction among genes, environment, and disease is very complex, eluding facile, definitive answers.

An ethical imperative

We already know that environmental inequalities impact at-risk racial populations (such as those in the US defined as African Americans, Hispanics, Native Americans, and Pacific Islanders. This does not negate the likelihood that ancestry influences disease prevalence within these groups or in response to treatments. But this is an empirical question that can be answered only by studying group differences carefully and comprehensively.

While age, geography, and co-morbidities are major risk factors in contracting or dying from COVID-19, the insights from genetic research are invaluable if we are to effectively tackle this and future pandemics. A growing wealth of data suggest population-level differences—which often do not neatly correlate with popular notions of race—can help us identify susceptibility or resistance to some diseases.

A failure or refusal to explore this extraordinary phenomenon borders on scientific malpractice, some researchers have told us. By not focusing on the actual science, we are denying the world the fullest understanding of how virus susceptibility works. More importantly, if we followed the “race-related” scientific leads, using the latest genomic data, we could very well come up with measures to better protect most of the rest of the world from COVID-19 and future virus-driven pandemics.

With Africa in particular, the vast genetic diversity within the continent is already revealing much about humanity’s long and deadly evolutionary duel with this scourge. What is more, African researchers themselves are adding to this growing wealth of knowledge, and in some cases taking the lead in population-genetic focused research. This will provide tools to one day eradicate many other diseases that take such a heavy toll on Africa’s peoples.

There are critical genetic differences in responses to disease and treatments; some are meaningful. Incorporating them into our health assessments can mean the difference between life and death for the most vulnerable. We ignore them at the peril of the health of billions of people.

- Source : Jon Entine and Patrick Whittle